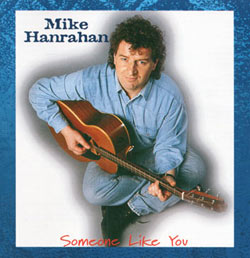

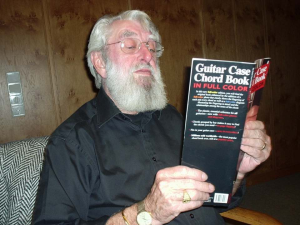

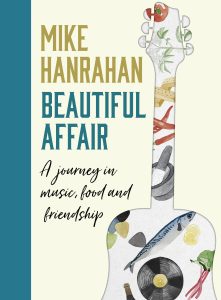

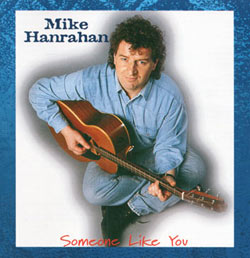

Author, Songwriter, Guitarist, Producer

Recent News

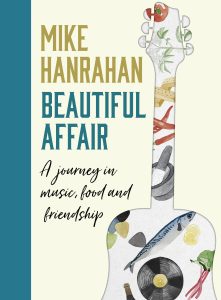

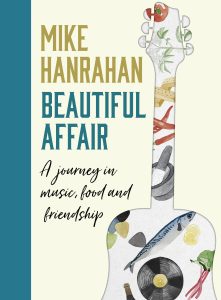

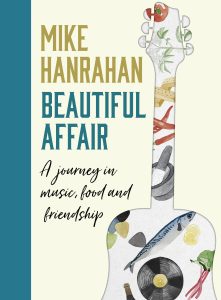

“ This book… it’s literally a beautiful affair. … I thoroughly loved this. It’s a very special piece of work.”

Critically acclaimed Hit TV show ‘Songs of Ireland’ Released April 27th. TV series filmed with Actor/Comedian Pat Shortt. A Concert tour expected late 2024

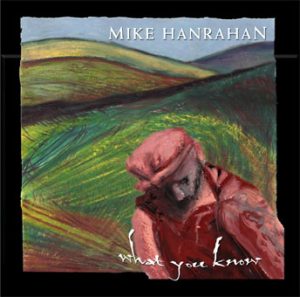

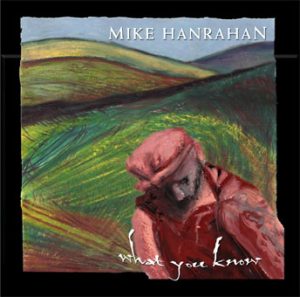

who recently signed to Tara/Universal Ireland releasing a back-catalogue collection of 42 tracks called Stockton’s Wing ‘Beautiful Affair A Retrospective’ followed by a live album ‘Hometown‘.

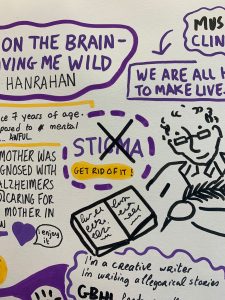

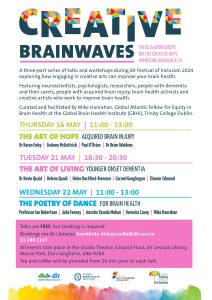

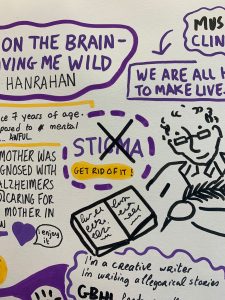

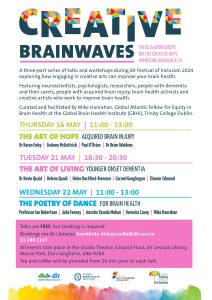

Just Completed a Fellowship and Post Graduate Certificate in Equity and Brain Health at The Global Brain Health Institute, Trinity College Dublin. Currently Exploring the development of Creative Arts in Dementia Care

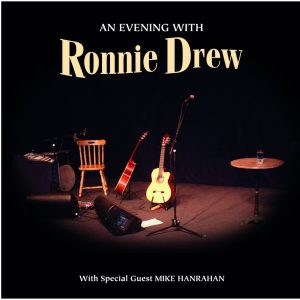

Lots of shows with Eleanor Shanley coming in. A few new gigs with Pat Shortt to celebrate our new TV series Songs of Ireland and Stocktons Wing are in for a few live gigs too...